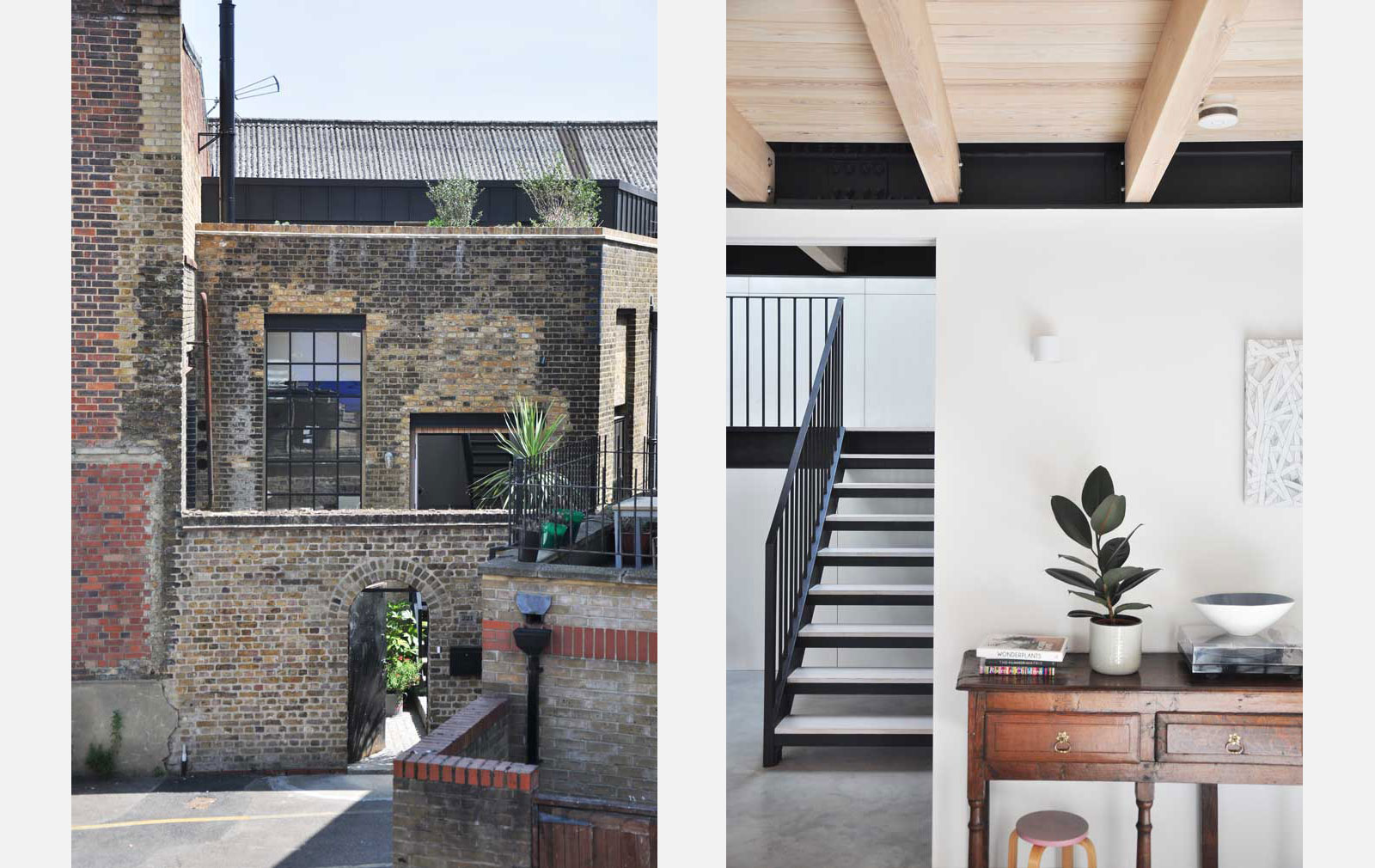

You might think you’ve taken a wrong turn when approaching the London home of architect Rupert Scott and coworking entrepreneur Leo Wood. The former gin distillery is tucked down a lacklustre side street in Whitechapel, beside a car park and a fabric warehouse. Just a palm tree peeking out above a brick wall hints at the oasis within.

Step through the arched metal gate and you’ll find a courtyard filled with greenery. A steel staircase leads up to a light-filled, double-height living space that feels a world away from the hubbub of Whitechapel.

‘Part of the appeal of the building was the idea of creating an enclosed, hidden enclave filled with plants,’ says Leo.

The couple were living nearby when they discovered it was for sale, but it was a prospect most people would have passed up.

‘When we found the building, it was just a derelict brick box,’ says Rupert, founder of Open Practice Architecture. ‘It was dark, skanky and very overlooked, but we could see the potential.’

Rupert gutted the building, retaining just the brick walls and concrete floor, creating a new steel-framed space within its restored envelope. The floor plan is shaped like a cake slice, with its point chopped off. The main, open-plan living space is at the narrower front, while a study and family room sit at the back. On the first floor, bedrooms extend up above the parapet line, peeking out across a terrace.

‘The biggest challenge was bringing light into the building while controlling the views,’ Rupert explains. He carved another terrace into the darkest corner at the back of the building, which bathes the bedrooms and steel staircase in light. New Crittal windows recall the structure’s roots.

Humble materials like concrete and pine have been used throughout. ‘I always try to avoid expensive, flashy materials, preferring simple ones that are carefully composed,’ he adds.

It’s an ethos that resonates with Leo, who has honed her design talents at her two east London coworking spaces and now her home. ‘One of the things I love is thrift – sourcing furniture cheaply at antiques fairs, or on Gumtree and eBay,’ she says. Her home is filled with carefully curated mid-century and contemporary finds, brought to life with colourful fabrics.

Fuelled by this project, Leo has launched her own interiors company, Kinder Design, and has recently completed another London coworking space – this time for a client. ‘I’m interested in the spatial balance of work, life and play,’ she explains. ‘I examine how people inhabit and use space.’

To this end, the gin distillery acts as a design manifesto for both Leo and Rupert, while being a frame for family life with their two young daughters. We spoke to them about their experiences of living in their own creation – and about future projects.

What does a home mean to you?

Leo: A place to feel safe, relaxed and comfortable.

Rupert: For me, it’s a vessel for stories. The longer you live somewhere, the more history you create there. We’re building on this structure’s existing story. Although we’ve completely transformed it, we’re just custodians of it. This will be a place full of memories for us and our kids.

Rupert, what was it like having your wife as your client?

It worked really well. We set things up like a conventional commission. I wrote emails to Leo as if she was any other client. But it was a joint venture. Leo helped with a lot of the cost management, the council admin, and all of the sourcing of furniture and fabrics, so I became her client for that.

Leo, what have you learnt from the project?

It’s been really formative for me. I’ve developed my eye for furniture and colour. It’s a constant tweaking process. I’ve realised how essential landscaping and greenery are to architecture. If you took away the plants, this would be a very different place.

Have you taken lessons from this project that you’d use in future coworking spaces?

Leo: Definitely. One of the things that I’m good at is tight budgets and I made my first two coworking spaces with no money at all. But if I was designing them now, I would invest in a slightly higher spec to create something more extraordinary. And I’d use more plants, be bolder with colour, and have a bit more of a design strategy.

Rupert, what appealed to you about transforming an old industrial building?

When designing a project, I find it easier to push against some sort of constraints – in this case, the original fabric of the building and the tight plot. I think that there’s something exciting about creating modern architecture within a historic context.

What does it say about your design ethos and wider practice?

It’s clarified a few things to me about who I am as a designer. What I’ve realised is that I’d never design anything for anyone else that I wouldn’t want to live in myself. I’ve developed a love for conservation – caring for old buildings, and the city in general. My practice is about using simple materials, honestly and well, with careful detailing, but not allowing the building to dominate. It’s there for you rather than the other way round. Good architecture is about framing things, family life, but also greenery and plants, and views – what you see and what you don’t.

How has the experience of living in the house differed from what you expected?

Rupert: When you do a self-build project, it takes ages to let go. It took me six months to start feeling relaxed here. It was like living in a work project, that you’d poured so much love and energy into. Then suddenly I started to really enjoy it.

What are your favourite spaces in the house?

Leo: I love the office – a space where I can sit at my laptop and do my work away from the kids. It’s my hub.

Rupert: For me it’s all about the front spaces – either sitting on the steps in the evening sun or being in the double-height space, which is still connected to the outside.

Rupert, what building has most inspired you in your lifetime?

The Ronchamp chapel by Le Corbusier is such a clever piece of architecture. It’s a composition, really. The quality of light is incredible. It has this amazing half light, like you’re in a forest.

Leo, if you could live in any other building besides this, where would it be?

We once visited the incredible Capel Manor House, designed by Michael Manser in Kent. It’s a modernist, 1970s glass box built on the site of a Victorian mansion, within amazing grounds. You feel like you’re part of the garden.

What’s your next venture?

Rupert: We recently bought an old coach house in Forest Hill, which we’re in the process of getting planning permission to transform into a three-bedroom home.