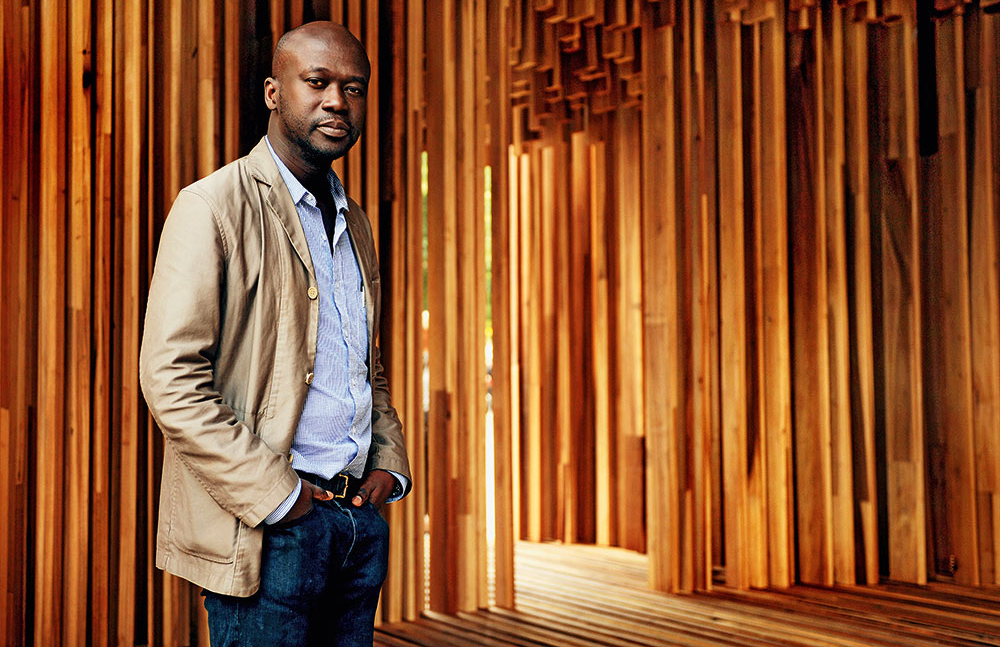

Sir David Adjaye made history last week, becoming the first Black architect to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal for Architecture by RIBA in its 173-year history.

The accolade is the Oscar of architecture and recognises not only the British-Ghanaian maverick’s incredible contribution to the world of architecture and design – it also signals a reckoning within the British architecture establishment, where less than 2% of registered architects are Black.

Adjaye has worked tirelessly for the last 27 years, taking on projects that range from monumental public scales to intimate domestic spaces, each with an instantly recognisable aesthetic.

‘His work is local and specific, and at the same time global and inclusive,’ said the RIBA president, Alan Jones in a statement about Adjaye’s 2021 Gold Medal win. ’Blending history, art and science he creates highly crafted and engaging environments that balance contrasting themes and inspire us all.’

Here are just a few of Sir David Adjaye’s key projects that demonstrate his importance to the world of contemporary architecture.

Elektra House, East London

Constructed between 1999-2000, the Elektra House was David Adjaye’s first built project – a giant lightbox at the west end of a 19th-century row of Victorian Houses in London’s Whitechapel. The building is on the site of a former single-storey workshop, references to which can be seen in Adjaye’s update. The height of the facade is the same as the neighbouring houses but has the appearance of being single storey. Inside, spaces are designed for displaying and creating art, with rooms illuminated by roof lights. The house is very insular with the only view of the surrounding neighbourhood visible from the top of its staircase.

Photography: Lyndon Douglas

Dirty House, East London

Artists Sue Webster and Tim Noble commissioned Adjaye to design The Dirty House for them as a home and studio in Shoreditch, adapting an existing pub on the site in 2002. The building’s brick shell is painted black, while its windows have been ‘filled’ with black mirrored glass to create an impenetrable and private facade.

The studio occupies the older building, while the new top floor houses living spaces including three bedrooms and a large roof terrace.

Photography: Lyndon Douglas

Dirty House, East London

Artists Sue Webster and Tim Noble commissioned Adjaye to design The Dirty House for them as a home and studio in Shoreditch, adapting an existing pub on the site in 2002. The building’s brick shell is painted black, while its windows have been ‘filled’ with black mirrored glass to create an impenetrable and private facade.

The studio occupies the older building, while the new top floor houses living spaces including three bedrooms and a large roof terrace.

Photography: Ed Reeve

The Stephen Lawrence Centre, South London

Opened in 2007, The Stephen Lawrence Centre in Lewisham is part memorial, part educational facility dedicated to helping young Black people in South London achieve their goals. The community space contains a coworking studio for local entrepreneurs, and is the hub for educational programmes for schools that support the UK’s BAME population to further their careers. The facility is an integral part of the community, and pays homage to Stephen, who dreamt of becoming an architect but was murdered in an umprovoked racial attack aged just 18.

Photography via Adjaye Associates

Sunken House, East London

Named for its semi-subterranean design, Sunken House in Hackney is a three-storey home in the De Beauvoir conservation area. The site was excavated down to basement level to create a patio base on which the partly prefab structure was placed. All facades of the house, as well as the vertical and horizontal surfaces of the concrete patio, are clad in a black rainscreen giving the appearance of being a solid block that encloses open and closed spaces across the building.

Sunken House, East London

Named for its semi-subterranean design, Sunken House in Hackney is a three-storey home in the De Beauvoir conservation area. The site was excavated down to basement level to create a patio base on which the partly prefab structure was placed. All facades of the house, as well as the vertical and horizontal surfaces of the concrete patio, are clad in a black rainscreen giving the appearance of being a solid block that encloses open and closed spaces across the building.

Sugar Hill, New York

Affordable housing sounds like an oxymoron in today’s economic climate, but in 2002, David Adjaye set out to rethink the typology of this type of urban development in the heart of gentrifying Harlem. The complex combined affordable units, including those for the city’s homeless, with a preschool and 17,000 sq ft cultural museum – the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling.

‘My hope is that the building—perched high on Coogan’s Bluff—will offer a symbol of civic pride and be a valued new resource for the neighborhood,’ explained Adjaye.

The 13-storey building’s brooding black exterior is typical of Adjaye’s work, and sits sympathetically within Harlem’s Gothic revival style low-rises.

Sugar Hill, New York

Affordable housing sounds like an oxymoron in today’s economic climate, but in 2002, David Adjaye set out to rethink the typology of this type of urban development in the heart of gentrifying Harlem. The complex combined affordable units, including those for the city’s homeless, with a preschool and 17,000 sq ft cultural museum – the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling.

‘My hope is that the building—perched high on Coogan’s Bluff—will offer a symbol of civic pride and be a valued new resource for the neighborhood,’ explained Adjaye.

The 13-storey building’s brooding black exterior is typical of Adjaye’s work, and sits sympathetically within Harlem’s Gothic revival style low-rises.

Photography: Wade Zimmerman

Lost House, Central London

While he has designed a number of private homes, it’s seldom that a David Adjaye-designed home hits the market. His King’s Cross project, Lost House, is among the rare few that have changed hands since being constructed, and this 2004 property occupies what was originally an alleyway in the neighbourhood.

Like a jewellery box, it hides its contents from prying eyes through the use of a modest brick facade that has one external window. The main interior volume is illuminated by three light wells that run the length of the space, diffusing natural light throughout its inky black interior. A number of internal courtyards bring a sense of the outdoors in, and add to the feeling that the house is a private oasis hidden from the world.

Photography: The Modern House

Lost House, Central London

While he has designed a number of private homes, it’s seldom that a David Adjaye-designed home hits the market. His King’s Cross project, Lost House, is among the rare few that have changed hands since being constructed, and this 2004 property occupies what was originally an alleyway in the neighbourhood.

Like a jewellery box, it hides its contents from prying eyes through the use of a modest brick facade that has one external window. The main interior volume is illuminated by three light wells that run the length of the space, diffusing natural light throughout its inky black interior. A number of internal courtyards bring a sense of the outdoors in, and add to the feeling that the house is a private oasis hidden from the world.

Photography: The Modern House

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

Adjaye’s most public, and arguably most important architectural project can be found in Washington DC. The Smithsonian National Museum for African American History and Culture sits on the National Mall, and is dedicated to telling the story of America’s Black citizens, from the impact and legacy of slavery through to the celebration of Black culture today.

To create the colossal 313,000 sq ft building, Adjaye looked to West African culture to inspire its three-tiered form, which references a Yoruban caryatid – carved wooden column with a crown at its peak. Aluminium-cast screens (or brise-soleils) decorated with historical patterns forged by African-American ironworkers in the South, shield the building’s glass facades and create shadow-play inside the cavernous building.

Courtyards are a recurring feature of Adjaye’s spaces, and the NMAAHC takes this to a new level with the powerful Contemplative Court. An oculus opening feeds a cylindrical waterfall and a reflection pool, flanked by stone benches. Here visitors can pause and process information from the exhibition halls below, which explores the enslavement and exploitation of African Americans. Upper rooms are dedicated to celebrating contemporary Black and African American culture.

‘Winning the project changed my career, and completing it has dominated my working life ever since,’ he told GQ magazine. ‘There were so many attacks on our design that it felt like a bloodbath at times. But we ended up with a building that’s got 90 per cent of what we wanted, which for architecture is pretty damn great.’

Photography: Brad Feinknopf

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

Adjaye’s most public, and arguably most important architectural project can be found in Washington DC. The Smithsonian National Museum for African American History and Culture sits on the National Mall, and is dedicated to telling the story of America’s Black citizens, from the impact and legacy of slavery through to the celebration of Black culture today.

To create the colossal 313,000 sq ft building, Adjaye looked to West African culture to inspire its three-tiered form, which references a Yoruban caryatid – carved wooden column with a crown at its peak. Aluminium-cast screens (or brise-soleils) decorated with historical patterns forged by African-American ironworkers in the South, shield the building’s glass facades and create shadow-play inside the cavernous building.

Courtyards are a recurring feature of Adjaye’s spaces, and the NMAAHC takes this to a new level with the powerful Contemplative Court. An oculus opening feeds a cylindrical waterfall and a reflection pool, flanked by stone benches. Here visitors can pause and process information from the exhibition halls below, which explores the enslavement and exploitation of African Americans. Upper rooms are dedicated to celebrating contemporary Black and African American culture.

‘Winning the project changed my career, and completing it has dominated my working life ever since,’ he told GQ magazine. ‘There were so many attacks on our design that it felt like a bloodbath at times. But we ended up with a building that’s got 90 per cent of what we wanted, which for architecture is pretty damn great.’

Photography: Brad Feinknopf

Ruby City, Texas

San Antonio’s Ruby City is a pink-hued arts hub with 10,000 sq ft of exhibition space for the city’s burgeoning creative scene. It is the brainchild of the late artist, philanthropist and collector Linda Pace, who donated her private collection of 800 paintings, video works, sculptures and installations to form the core of the museum’s displays.

Adjaye’s main building forms the heart of a growing ‘campus’ of buildings for the creative community, which also includes Chris Park – dedicated in honour of Pace’s late son.

The architect conceived the building less as a physical space and more as an experience: the museum unfurls as an ‘ambulatory loop’ that moves visitors up and through the gallery rooms before depositing them back down in the lobby and plaza.

Photography: Dror Baldinger

‘City Dreamers’ celebrates the lives of four iconic women architects